German sport sociologist Robert Gugutzer discusses the role of the body in modern society.

Robert Gugutzer

Robert Gugutzer is a sports sociologist and the leading researcher in Germany in the field of body, sports and wellness. Gugutzer is professor at the Institute of Sports Sciences of the Goethe-Universität Frankfurt. He is known for comparing the cult of the body in contemporary society to a modern form of religion.

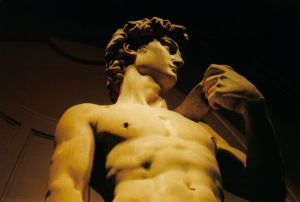

Eternal ideal? David by Michelangelo

Photo: stock.xhng

What role does the body play in society today?

A historical comparison shows unequivocally that overall, the body has gained in importance in societies such as ours. This does not, of course, mean that the body was of no significance in the past for people or their life together. On the contrary, it can be said that the body was once even far more important in some areas, such as that of work. Today it is a well-known fact that far fewer people carry out such hard physical work than in premodern societies. After all, we live in a “sedentary” society in which most work is carried out with the body remaining relatively “uninvolved”. This means that the body has certainly lost some of its value today.

At the same time, however, and this is something which is especially noticeable, a rise can be seen in the value that society places on the body. This is due in particular to growing material wellbeing, the drop in the significance of church religions, the growth in the leisure sector, the implementation of post-materialist values and the development of the mass media. These social developments have led to the body becoming increasingly important for our own identity work: we take part in sports, look out for our physical health, watch what we eat and spend a lot of time and money looking after, decorating, pampering and beautifying our body, taking advantage of all kinds of technologies to modify and improve it – all of which we do for our own good; for our self. Moreover, as there is more discussion on body-related topics and the body is increasingly visualised, it can certainly be said that the body is today more strongly at the focus of social attention than in the past.

According to what patterns do we perceive others’ bodies; who do we find especially attractive and who not?

Very generally speaking, the patterns which determine how we perceive the body have evolved historically and thus vary according to culture or social structure. Or, as the British social anthropologist Mary Douglas wrote long ago, “the social body constrains the way the physical body is perceived”. As a consequence, people value physical appearance in different ways depending on the time, culture and social setting in which they grow up or live.

Thus there is on one hand a socially dominant, general image of physical attractiveness, and on the other hand, existing beneath, or alongside it, a range of socially and individually different ideas of what is attractive. For this reason it is hard to make any general statement on who “we” find attractive, because who are “we”?

Does outward appearance affect the persuasive power and effectiveness of teachers or lecturers in education?

Many social psychology studies have discovered that attractive people are at a professional advantage: they stand a better chance in interviews, are judged to be more competent and are sometimes even paid more. For this reason it is fair to assume that the appearance of teachers and lecturers plays a similar role in an educational setting. Here too, there is likely to be a positive link between appearance and ascribed (not actual!) skill: the more attractive they are, the smarter people think they will be.

I would, however, say that there is a limit after which an attractive appearance is no longer a guaranteed bonus but may in fact even have the opposite effect, acting as a drawback. If you are “too” good-looking you might involuntarily deflect attention from your professional skills (by sparking envy because people cannot believe anyone could be both attractive and clever). Above all, however, attractiveness is most likely to have a negative effect when it is obvious that a teacher or lecturer has invested a lot of effort, time and – worst of all! – money in his or her appearance: all in all, attractiveness is only truly appreciated when it is “natural” and not artificial; the result of 30 hours a week in the gym or various kinds of cosmetic surgery. The fact that there is no such thing as natural beauty, as everything about our body is a social “construct”, as sociologists put it, plays no role in this judgement.

Is it possible not to be affected by the ideal image of the body portrayed in advertising and the media?

We live in a thoroughly media-saturated society, whose images we cannot escape in practice. Newspapers and magazines, films, the television, the Internet and posters are full of images of the body which infiltrate our minds even though we may not be aware of it. As already mentioned, our social body affects how we perceive our actual body and those of other people.

The things we do with our body are thus related to dominant ideals regarding the body and attractiveness. At the latest, this becomes apparent when other people point out (to put it nicely) that we do not live up to physical standards in a certain context. However, this does not mean that we necessarily have to submit to those standards. Everyone is free to say no.

In the eyes of the philosopher Ernst Tugendhat, being able to say no in the face of social expectations is a moment of self-determination that is important for one’s personal identity. To become a “free” individual, Tugendhat posits, one has to learn to say yes and no not only to others’ imperatives but also to one’s own aspirations. This is equally true of the dominant imperatives regarding the body with which we are all confronted. As these imperatives can now hardly be eliminated, or certainly not immediately or any time soon, our only remaining option must be to practise saying no. After all, the glittering reward for such asceticism is personal freedom. And that is a reward worth winning.

This article is produced in cooperation with the InfoNet adult education correspondents’ network.