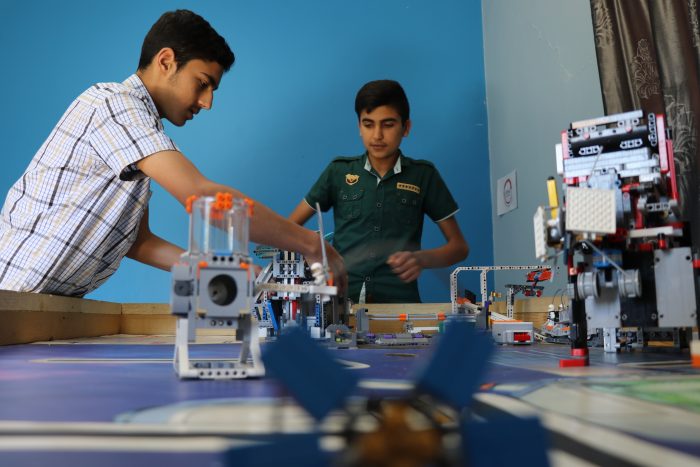

MAP’s courses for continuous education encourage learning that is based on creativity and innovation. Photo: MAPs

MAP’s courses for continuous education encourage learning that is based on creativity and innovation. Photo: MAPs

The job of teaching in a refugee community is full of challenges. The Lebanon-based Syrian organisation Multi Aid Programs trains both children and adults to cope with daily life but also prepares them for a brighter future.

Fadi Al Halabi fled his homeland of Syria to neighbouring Lebanon early in 2013. Al Halabi is a trained neurosurgeon. In Lebanon, he encountered something that changed the direction of his life – approximately 250,000 school-aged Syrian children without schools.

“I began to think that I did not want to just work as a doctor and serve patients. I decided to work for the benefit of my community on a strategic level.”

Al Halabi established the Multi Aid Programs (MAPs) organisation with another Syrian doctor, Mouhammed Al Masrin. The organisation offers education, training and health care to Syrian refugees living in Lebanon. The aim is, however, much greater than just meeting the basic needs of people.

“We want to create something valuable for our community.”

“People have the right to be themselves but, because of the circumstances, people tend to think only about basic needs,” says Fadi Al Halabi. In his opinion, refugees should take responsibility for their own communities but, in a difficult situation, help is also needed from outside. Photo: MAPs

All projects look to the future. The teachers at MAPs’ school, all of whom are Syrian, have received and are receiving training. The training includes teaching methods that place the children and their feelings and ideas at the forefront. In Syria, children would generally just learn by heart what their teachers said.

In MAPs, it is thought that by developing creativity, problem solving, emotional literacy and cooperative skills, children will cope better, not only with daily life in refugee camps but also in the future reconstruction of their homeland.

Teachers teaching each other

The education specialist of the MAPs organisation is Brian Lally who comes from Great Britain. When he began working for MAPs some four years ago, the training of teachers was among his first tasks. “Only some of them had worked as teachers before.”

Others had been engineers and lawyers. They were beginning to teach for the first time in their lives, and needed training in the basic things such as lesson planning. With the experienced teachers, it was not worth spending time on things like that. In order to resolve individual challenges, Lally sat in on the lessons and coached the teachers after that.

Something that was new for everybody was working with children who were fleeing from war. The teachers had to learn to recognise trauma and to give psychosocial support to the children. At the same time, it was important to learn to distinguish their own responsibility as a teacher from other responsibilities towards to the children. It is not necessarily easy, caring about the children and knowing that life outside school is very difficult for them.

Our schools are therefore movable containers. We convey to the children the idea that these are actually their schools and they will be transferred to Syria once the crisis is over.

MAPs has nine schools in Lebanon. They are situated in the areas of the Beqaa Valley and Arsal either in the refugee camps or in their immediate vicinity. The younger children receive teaching in the morning and the older ones in the afternoon. Lally still visits the classrooms to monitor the lessons. In recent years, however, the focus has moved to the teachers following each other’s lessons and thus learning from each other.

In addition to their work, the teachers have also done practical research. They have identified their own teaching challenges. After that, they have considered solutions and tried them out in their lessons. Good practices are written down and shared with colleagues. “This project has been decisive to the professional development of teachers,” Lally confirms.

Brian Lally was previously headteacher of a high school in Great Britain. Courses that he took at University College London dealing with the situation of refugees and work in areas of conflict resulted in his work at the Syrian organisation in Lebanon. Photo: Hanna Hirvonen

The project has accumulated knowledge about courses there is a need for. Since the beginning of the year, for example, teachers have gone through evaluation models. Because of the coronavirus, there has been a break in training and schools are closed. The teachers keep in touch with families in WhatsApp groups in which school exercises are distributed.

The situation is worrying as everyone knows how difficult it is to study in the cramped conditions of a refugee camp. Home is often just a makeshift tent and large families live in small spaces.

Dreams of returning to Syria

Approximately 1.5 million Syrian refugees live in Lebanon. The Lebanese government has begun to pressure them into returning to their homeland. Their lives have been made difficult by restricting their working opportunities and destroying their homes in Lebanon. MAPs emphasises that the Syrians are just visiting Lebanon, and that most of them dream of a return to Syria.

“Our schools are therefore movable containers. We convey to the children the idea that these are actually their schools and they will be transferred to Syria once the crisis is over. Our message to the Lebanese too is that we are visitors here,” says Fadi Al Halabi.

A return to Syria would not be safe at present.

According to Al Halabi, people should try to remain active. The worst thing is just having to settle for waiting – waiting for peace in their homeland, assistance from an international organisation or perhaps a visa to Europe.

“In my opinion, we must work in Lebanon as if we will always be here. At the same time, we must work as if we will be home tomorrow. I don’t just mean working in the job market. We must do something valuable for ourselves and for our community.”

The students are gaining a set of skills that will be beneficial both in Lebanon and in Syria.

Adults are doing professional studies through the organisation’s courses. The courses include nursing, web design and foreign languages. Thanks to the training, some people have begun business in Lebanon. At the same time, the courses are developing skills, which will later be needed to rebuild Syria.

“It is important to learn critical thinking and problem-solving. These can be practised on professional courses. By servicing a car, for example, you can see how the parts work together. At the same time, you can understand that, if you want to succeed, you should work together with others.

MAP’s courses for continuous education courses include nursing, web design and foreign languages. One of the projects is called Robotics Club. Photo: MAPs

University studies progressing during coronavirus

With the support of MAPs, 35 students are doing bachelor’s degrees organised by Southern New Hampshire University in the United States. Studying from Lebanon is possible because the degree can be studied for online. A positive surprise in the Syrian community during the time of coronavirus has been the progress of the studies of the university students.

“Many of them have made great progress. We’re talking about students aged 19 and above. At the moment, they cannot go to work which would previously have hindered their studies,” says Brian Lally.

The students have been given laptop computers and they have access to all the required material while studying for the degree. The students are reading three main subjects: business, communications and health care management. At the same time, the studies are developing their general abilities such as innovative skills. When studying online, the students must practise self-motivation and time management.

“The students are gaining a set of skills that will be beneficial both in Lebanon and in Syria.”

Graduates will perhaps be able to use the internet to find work outside Lebanon. Syria will need to have its health care system rebuilt. Companies will also have to be established in areas where everything must be started from scratch.

“Expertise related to business, communications and health care will be vitally important,” Lally says.

Author