Careerists or Educational Aspirants? – (Re-)entry of European Lifelong Learners into Higher Education.

Published:Little research exists on lifelong learners' motives for studying at university level. This paper fills this gap and gives LLL program designers important insight into learner profiles.

Introduction

In Europe recent socio-economic developments demand a more highly skilled workforce, which therefore needs higher qualifications and education. Not only should access to higher education be widened to include a greater variety of student groups like adult learners, vocational learners and employed learners, but the teaching-learning environments and the guidance should be adapted to the diversified needs of lifelong learners.

With the importance of lifelong learning rising and the expansion of mass education, discussion often refers to these learners as ‘non-traditional students’. But in the current literature this remains a rather vague and multidimensional concept and includes for example adult students, students belonging to equity groups, employed students or students coming through alternative entry routes (OECD, 1987; Davies, 1995; Kasworm, 1993; Crosling, Heagney & Thomas, 2008; Slowey & Schütze, 2000; Horn & Carroll 1996 or Schuetze & Slowey, 2012).

The focus of this article is on lifelong learning and therewith we adopt the concept of the ‘lifelong learner’ developed by Müller and Remdisch (2013), rather than use the less specific term ‘non-traditional student’. The lifelong learner in our study is predominantly characterised by having vocational experience, i.e. a learner with vocational education or with 2 years or more of working experience before entering university. These students are often aged 30 and over, learn in study formats other than contact study and work full or part time while studying. Therefore late learners, alternative learners and employed learners are also included within the concept of the lifelong learner.

By using the concept of the lifelong learner, we wanted to differentiate our focus from those fields of research that use the term “non-traditional students” for equity groups or other non-traditional characteristics since this is not the scope of our article. Additionally, the number of non-traditional students is constantly rising at European universities, turning them into traditional students. Thus the concept of the non-traditional student is no longer very distinctive. Therefore we refer to “lifelong learners”, since in our opinion this best captures the group of students we are focusing on: those who enter or re-enter university for further qualification or requalification.

But why do these lifelong learners (re)-enter university and what types of lifelong learners are higher education institutions receiving at the moment? Little is yet known about their range of motivations although it is of great importance. Allen (1999) argues that motivation can be seen as a form of goal commitment and a strong desire for achievement. This offers interesting insights for higher education policy makers and program designers into the motivations for lifelong learners to come to university.

To summarize these aims, goals and motivations to make them more tangible, a typology of lifelong learners is developed based on theoretical and statistical analysis. The data used was conducted at three European universities who each have a special model to integrate lifelong learners (for a detailed description see Köhler, Müller & Remdisch, 2012). There are some national studies developing typologies of lifelong learners or respectively non-traditional students but they either lack motivation as a distinguishing factor and/or are not of comparative nature. Therewith this article fills an important research gap.

Models of University Lifelong Learning

With LLL emerging as a key theme in the European higher education area, the project ”Opening Universities for Lifelong Learning“ was established. This work is part of the second project phase in which good practices of university lifelong learning models were analyzed and data on lifelong learners was collected. The three institutions selected all had different approaches for how to adapt to the needs of lifelong learners (Köhler, Müller & Remdisch, 2012).

As a result of the merging process between the University of Lüneburg and the University of Applied Science of East Lower Saxony, the Leuphana University of Lüneburg (Leuphana) in Germany refounded itself in 2006 and created a new university profile which is, so far, unique throughout Germany. The university was re-organized into three teaching bodies – the College, the Graduate School and the Professional School – complemented by a house of research. The data used for this study was collected at the Professional School, which offers several undergraduate degrees and postgraduate degree programmes targeted at employed and vocational learners and using contact, blended and distance learning formats. In essence, the delivery of LLL at Leuphana is centered in a separate school, the Professional School.

The University of Southern Denmark (SDU), on the other hand, has a different approach to meeting the needs of lifelong learners. As a part of their continuing professional development they have a unit directly targeting lifelong learners: the single course programmes and established programmes target employed learners within the existing university structure. Further, their decentralised campus structure attracts students from rural areas and has thus increased the participation rate notably.

The Open University of the Helsinki University (OU Helsinki) is one of the 15 Open Universities of Finland. The Open University offers courses in Finnish from nearly all of the faculties at the University of Helsinki. Although students cannot complete a whole degree at the OU, individual courses can be accredited towards degree programmes. The OU provides anyone with the opportunity to participate in university studies, regardless of age or educational background. The courses are designed to accommodate mature students and are organised mainly in the evenings and on weekends in distance and contact teaching formats.

Furthermore, it is important to mention that these institutions were selected on the basis that each is embedded in a different national context (based on Esping-Andersen, 1990 and Green, Preston & Janmaat, 2006). This allows for cross-country comparisons of lifelong learners in different contexts.

Germany belongs to the conservative welfare system/neo-corporatist core European model which is characterised by the principle of social stratification to ensure status for those in power. Within countries belonging to this system, lifelong learning and adult education is of minor importance. In contrast to that, in Denmark, which belongs to the social-democratic welfare states/Nordic model, the principle of universalism exists. Adult education and lifelong learning is of great importance. This is especially the case for Finland which was included as a second social-democratic country because here universalism and lifelong learning are even more deeply rooted in the social and political structure. Additionally, Germany is characterized by a selective secondary schooling process and strict separation between academic and vocational studies in comparison to the far more open systems in Northern Europe (Müller & Remdisch, 2013). Furthermore, there is less participation in HE in Germany because the vocational education system is actually preferred by those stemming from groups underrepresented in HE. In this context, opening universities increases second and third chances for university studies to a great extent and is therefore of special importance.

Typologies of Lifelong Learners

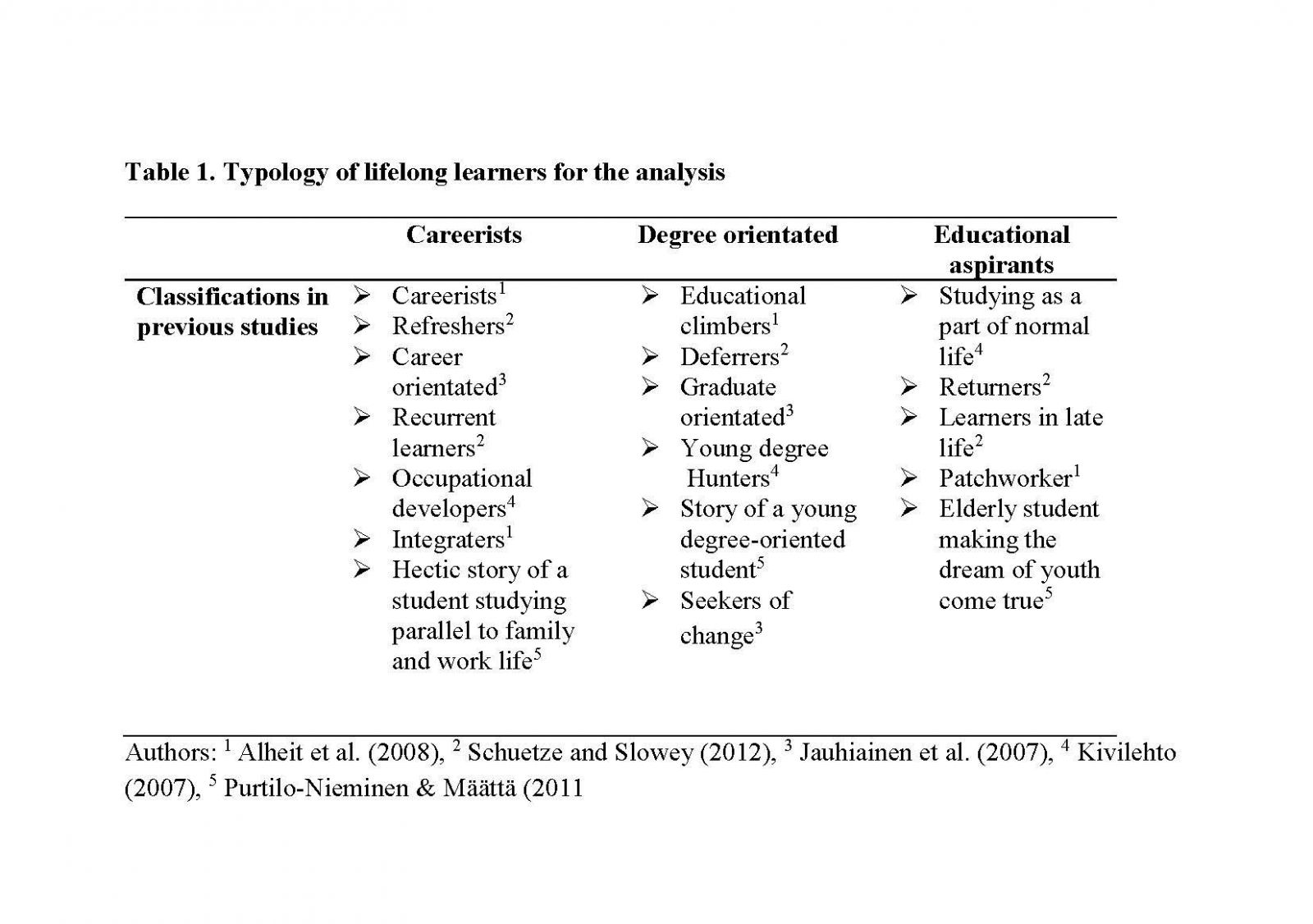

The current section reviews various typologies of non-traditional students applicable to our context. Based on these typologies, an own typology was developed to be tested empirically.

In the newest international volume by Schuetze & Slowey (2012, pp. 15–16), second chance learners, those without a traditional entrance qualification, and equity groups are to be found within the definition of non-traditional students. In contrast to their previous studies, Schuetze and Slowey put a major focus on the primary motivation to attain HE.

For the deferrers gaining an appropriate qualification is the major motivator.

The recurrent learners, who already have a first degree and return to higher education for a further, usually higher degree, are motivated to gain additional or different qualifications for employment purposes. Also interest in the subject is another reason for entering HE. Schuetze and Slowey further identified the returners in their international study. Returners are those who drop-in into higher education after having previously dropped out, and they see the higher education experience as woven into the fabric of their lives.

The refreshers, a category which partly overlaps with the former categories, are those who enrol in continuing education programmes to refresh their knowledge and skills.

Lastly, the learners in later life can be distinguished who in majority enrol in non-credit higher education programmes for personal, non-career development reasons. This typology is not based on an empirical analysis but rather on the discourse on types of non-traditional students to be found in various countries.

In the case of Germany, Alheit, Rheinländer and Watermann (2008) have identified four dominating profiles of experience for non-traditional students based on a qualitative biographic study with 112 students. The first empirically identified type is the “patchworker”. Patchworkers are good at starting new things but often lack long-term plans and continuity in their CVs. They further lack biographical reflexivity and the study is sceptical about their prognosis of success.

The next type, the “educational climber”, usually comes from a background distant from the world of education and strives for social change. The wish to study is a long-standing goal, which had not been realised because of various obstacles, and is resumed because of contact with the academic world. The aim of studying is not for social or vocational promotion but to take part in the world of the university and includes removal from old networks. This together with feelings of inferiority and uncertainty leads to high dropout rates.

“Careerists” on the other hand combine the programme/courses with previous qualifications, since their decision to study is based on clear career goals. They tend to be very successful and their study behaviour is fast, efficient and confident.

The last type, the “integrater”, see the programme as an opportunity, but while studying they remain rooted in their work/life backgrounds and relate least to the university world from which they stay distant. They are usually successful, with a positive prognosis for their studies, and see their studies as a way of improving their future career possibilities.

We are not aware of any comparable studies from Denmark. However in Finland, quite a few studies about lifelong learners’ goals and motivations have been carried out. Jauhiainen, Nori and Alho-Malmelin (2007) classified four student types, based on the analysis of 106 educational autobiographies and identified the career orientated, the graduate orientated, the seekers of change, and those for whom continuing to learn is a normal part of life. Kivilehto (2007) found three different Open University student profiles based on quantitative data of students’ age, educational background, approaches to learning and experiences of teaching-learning environments. The groups were occupational developers, young degree hunters, and adult learners. Purtilo-Nieminen & Määttä (2011) did narrative research on Open University students who started their studies in the Open University and then gained admission to fulltime university degree studies, transferring the Open University credits already earned.

Three typical narratives emerged. There is the story of a young degree student, the hectic story of a student who studies parallel to family and work demands, and of an elderly student making the dream of his youth come true. In another qualitative research study, Sirkkanen (2008) interviewed Open University students that studied in order to develop their professional competencies. In addition to offering a typology of discourses and reasons for university studies, this research concluded that the relationship between professional competencies and the motivation for studying is contradictory and varied. There is a complex tension between a student’s inner world and outer environment.

Existing empirical studies suggest that either clear career goals, an interest in the subject, or the desire for change and a degree for a current or new career are the main triggers. We identified three dominating profiles: the careerists, the degree orientated and the educational aspirants. As careerists we consider those who come to university motivated mostly to develop their professional competencies, as educational aspirants those who come to university because of interest in the subject and as degree orientated those who seek a degree for entering a new career/employment or just to finally have a HE degree. While some authors have developed subgroups or additional groups, according to our research, they can be summarized into these three groups (see Table 1).

Methodology

Participants

Students in lifelong learning formats at the University of Southern Denmark (SDU), the Open University Helsinki (OU Helsinki) and the Leuphana University Lüneburg (Leuphana) were asked to fill out a questionnaire about various topics regarding their studies. The Professional School at the Leuphana is of a small size and the survey here reflects nearly a complete sample. For the other universities the response rate varied between 21 percent for the OU Helsinki and 18 percent for the SDU. The majority of the respondents were women and the mean age was 37.9 years (see Table 2 for a description of the samples). Since the focus of the study is lifelong learners, the majority of the interviewees were vocational learners, here defined as those with a minimum of 2 years work experience or a vocational education.

.jpg)

Measurements

To get insight into the socio-demographic characteristics, the students were asked for their age and sex. The study conditions of the students were collected through various questions about their work situation (e.g. not working, working in full or part time while studying), the study format (e.g. contact study, distance study or blended learning), their work experience in years and whether they had a vocational education.

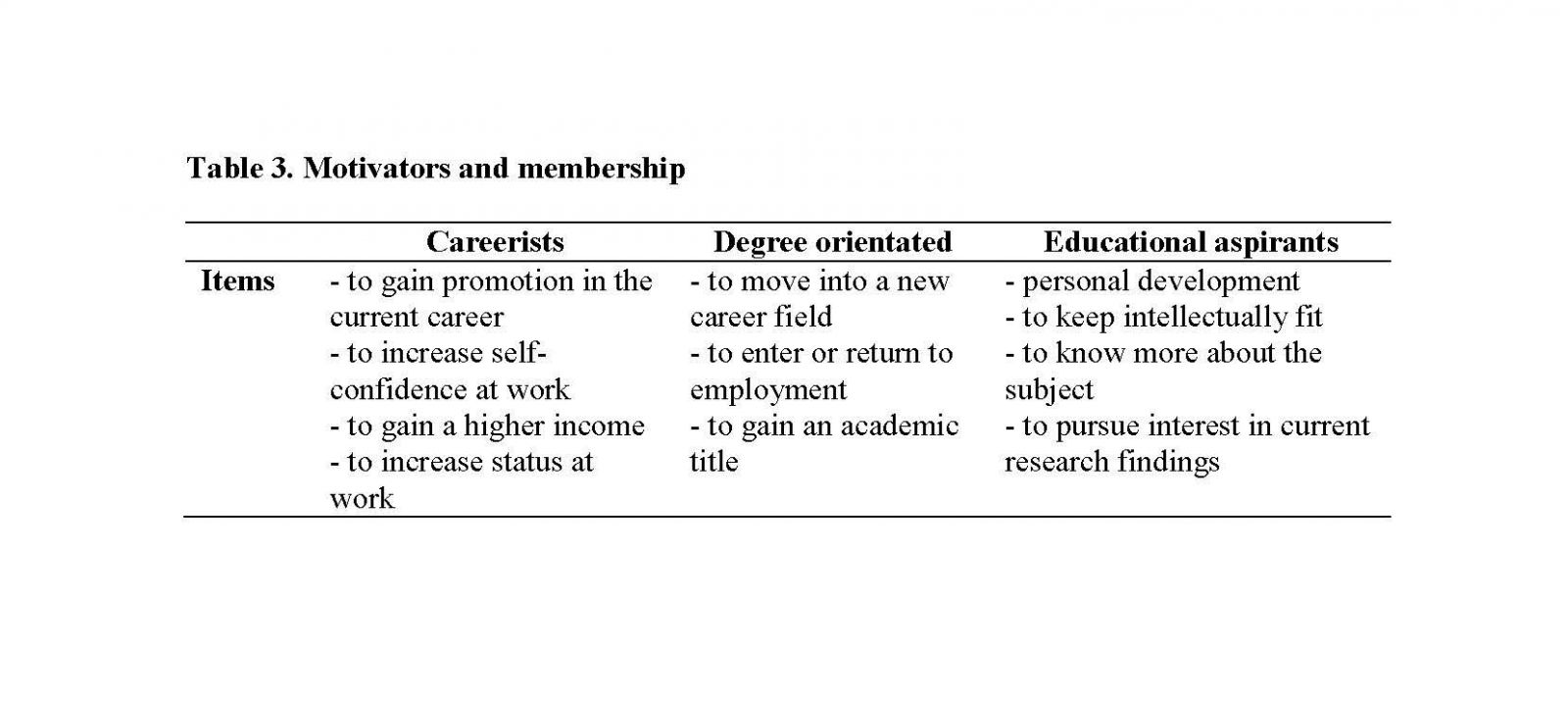

A scale was developed to measure the motives for studying for each of the aforementioned types of lifelong learners. The respondents rated these motives on a 5-point Likert scale with regard to how important each motive was in their decision to begin studying at their respective universities. The motivators were selected for this analysis based on what we identified as theoretically belonging to the three groups. Each motivator was sorted into the group where we assumed they would score highest, and are displayed in Table 3.

Research questions

(1) Does the data support our theoretical grouping of lifelong learners, i.e. can our groups be identified in the data?

(2) What type of lifelong learner is found most frequently in each country?

Statistical analysis

To build groups of lifelong learners, the theoretically identified motivation items were used to cluster the respondents. Cluster analysis is a method for forming groups of observations based on shared characteristics. Non-hierarchical cluster methods were considered best since we wanted to achieve a cluster solution with the number of our theoretically identified groups and, in contrast to hierarchical cluster methods, cases can be reassigned to other clusters to achieve the best three cluster solution (Hair, 2006).

The K-means clustering algorithm, where respondents are grouped into a fixed number of clusters to the cluster with the nearest mean, was applied to the data. Since theoretically it was assumed that there are three clusters, the number of clusters was fixed to three and the calculation was done separately for each country because of the assumed country and university differences. The variables were standardized with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 before the analysis to ensure easy interpretation of the results. When negative values occurred, the cluster was characterized by a low agreement to the presented motivation in comparison to the mean of the other clusters; and when positive values occurred, the cluster was characterized by a high agreement to the presented motivation in comparison to the mean of the other clusters. The clusters were then sorted towards the theoretically identified groups of lifelong learners based on the motivations where the highest values were to be found.

Results

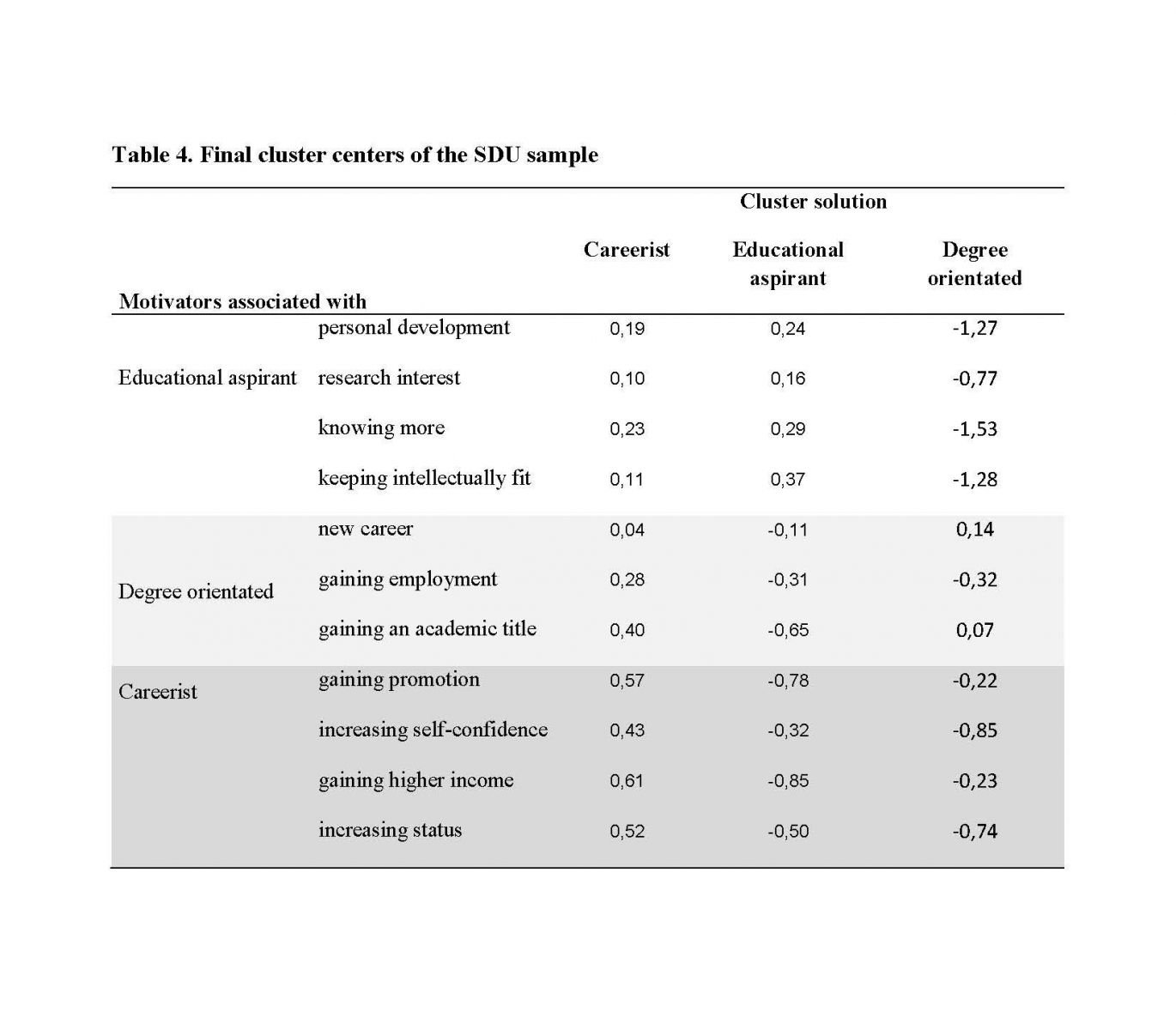

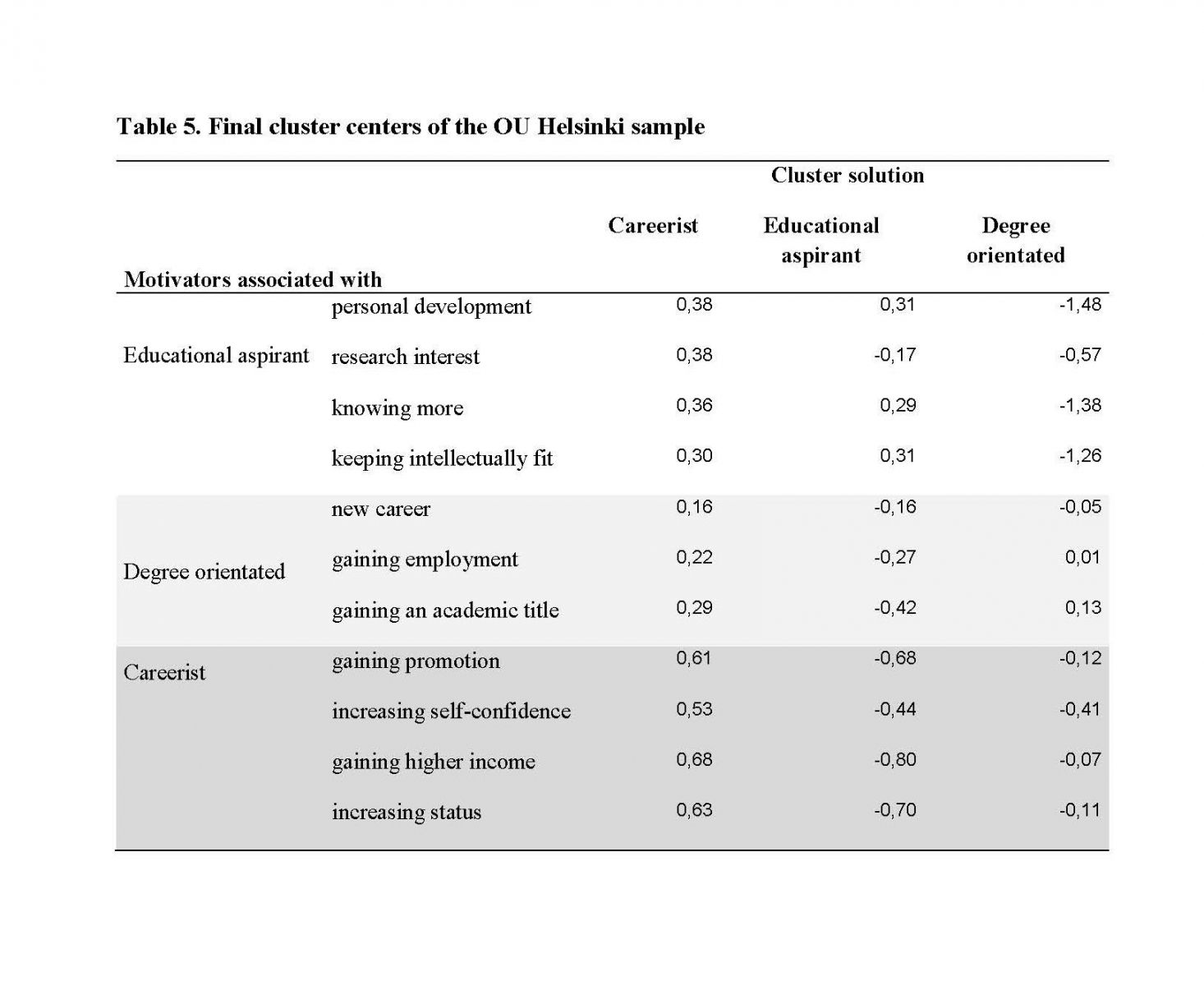

The cluster analysis was performed separately for each country. The variables associated with the careerist, except gaining self-confidence at work and keeping intellectually fit, contributed most to our cluster solution for the SDU and Leuphana. At the OU Helsinki, personal development, keeping intellectually fit and the career motives contributed most to the cluster solution. All variables had a significant contribution except for the variable “to enter or return to employment” in the SDU and Leuphana sample. This is not surprising since most of the students at these universities were employed students. This could be the reason why this variable was not as influential as the other variable to differentiate the clusters. In the following, the results of the cluster analysis are discussed, and therewith the types of lifelong learners prominent in the different universities are described.

Types of lifelong learners at the SDU

Table 4 displays the final cluster centers for the SDU sample. The final cluster centers were computed as the mean for each variable within each final cluster and reveal the characteristics typical for the three clusters.

The first cluster had positive values for all the variables. In comparison to the other clusters, this cluster had values above the mean for all variables associated with the careerist and was therefore called the careerist. Lifelong learners in cluster 2 and 3 had negative values on the career items.

The second cluster also had negative values on the items associated with the degree orientated but positive values on the items associated with the educational aspirant. It was therefore identified as the educational aspirant.

The third cluster had negative values on all items but starting a new career and gaining an academic title. In comparison to the other clusters, this cluster had the highest value on starting a new career and was therefore called the degree orientated. Some of these items were also important to the careerist, for example, gaining an academic title. But an academic title can be useful for both settings, e.g. to allow entry to a new career, or in the old workplace as a prerequisite for promotion. But given the fact that the third cluster had negative values on all other items and only the first cluster had positive values on the items associated with the careerist, the first cluster clearly reflects the careerist and the third cluster the degree orientated. Additionally, the people belonging to the first and second cluster were more motivated, as reflected by the high means, than those belonging to the third cluster.

The careerists constituted the biggest group within the SDU sample with 52.1 percent, followed by the educational aspirants with 33.5 percent. The smallest group was the degree orientated with 14.4 percent. Additionally, we also calculated the Euclidean distances between the final clusters. Greater distances reflect greater dissimilarities and smaller distances greater similarities. In the SDU sample the smallest distances were between the careerists and the educational aspirants, indicating that these two groups were most similar to each other.

Types of lifelong learners at the OU Helsinki

Similar to the SDU sample, the first cluster had positive values on all items (see Table 5). This is in contrast to the second and third cluster, especially in comparison to the items associated with the careerist. Here the first cluster had the highest and only positive values and therefore represented the careerist best.

The second cluster had negative values on all items apart from 3 out of 4 items associated with the educational aspirant and was therefore identified as this type of lifelong learner.

The third cluster had negative values on all items except for gaining employment and an academic title and was therefore identified as the degree orientated. Similar to the SDU sample, the careerists also had high, positive values on the items associated with these two types, but some of the items which could also be connected to career motives and career goals seemed not to be the only reason for this group to return to or enter university. Furthermore, the people belonging to the first and second cluster were more motivated, as reflected in the higher means, than those belonging to the third cluster.

The careerists and degree orientated constituted the majority with 44.2 and 36.7 percent. The degree orientated constituted the minority with 19.2 percent. When looking at the Euclidean distance, again the careerists and the educational aspirant were closest to each other and the degree orientated was most dissimilar to the other two clusters.

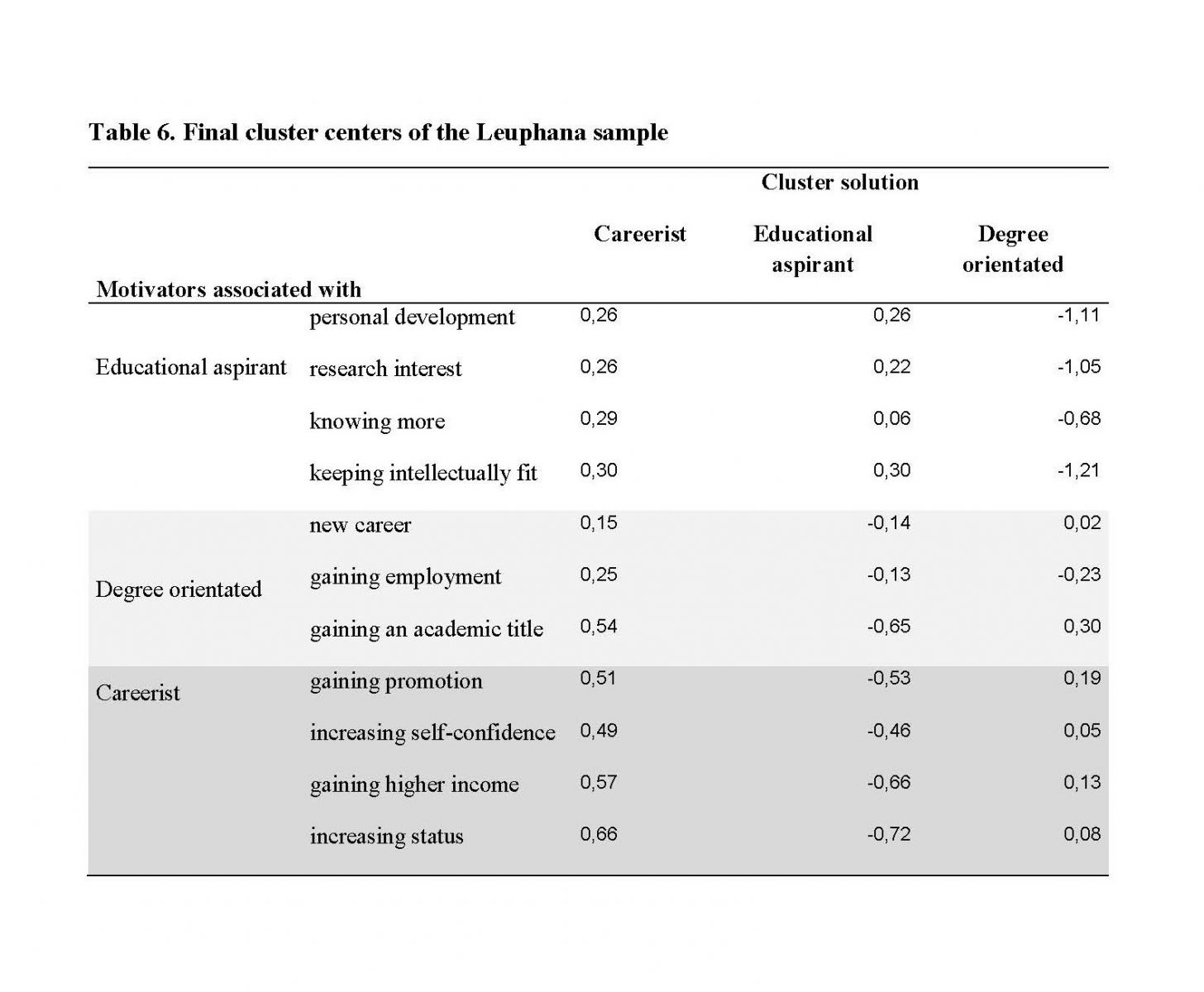

Types of lifelong learners at Leuphana

At Leuphana the cluster solution looks slightly different than in the other two samples (see Table 6). Similar to the SDU and OU Helsinki the first cluster had high values on all items and the highest values on the items associated with the careerist. It can therefore be identified as the careerist.

The second cluster had positive values only on the items associated with the educational aspirant and was therewith identified as such.

For the third cluster interpretation was not as easy as the results from this cluster analysis were different from the SDU and OU Helsinki.

The third cluster had positive values on entering a new career, gaining an academic title and the career items with higher values for gaining promotion, gaining a higher income and gaining an academic title. The value was highest for gaining an academic title and this cluster was therefore identified as the degree orientated. Similar to the other two universities, the people belonging to the first and second cluster were more motivated, as reflected in the high means, than those belonging to the third cluster.

At Leuphana the careerist and the degree orientated dominated, with each making up for 40 or respectively 41 percent of the total sample and were followed by the educational aspirants with 19 percent. Looking at the Euclidean distances, the degree orientated was most similar to the other two clusters, and the educational aspirant and the careerist were most dissimilar to each other.

Conclusion and discussion

To a certain extent we were able to identify all the groups we had theoretically assumed within the different samples. The careerist, the degree orientated and the educational aspirant were to be found in all countries but with differences regarding some characteristics and group size. The greatest dissimilarity between the different universities was observable for the degree orientated. For the German sample, gaining promotion and a higher income also had positive values in this cluster. This trend was not noticeable in the Nordic countries. A reason for that could be that, given the high share of females in the German sample, the gender pay gap is bigger in Germany than in Finland and Denmark (Eurostat, 2013). This trend for Germany is especially striking in leadership positions where women earn 30 percent less than men (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2010). In our sample, kindergarten teachers and similar professions where the great majority are female, and come to university to study social work or social management, are mostly found within the degree orientated cluster. Because of the divide in Germany between the vocational and academic world and a strong orientation towards degrees, an academic title is essential to become employed in leading positions within this area.

This could be one reason for the contrast to the Nordic countries and is supported by the fact that the Professional School in general has a major focus on career development. Another reason for the country differences could be that in the SDU and OU Helsinki sample the degree orientated constitute the youngest group. They seem to have more in common with the “traditional student”, who might be more degree oriented and less focused on personal development (Bye, Pushkar & Conway, 2007). Such age differences were not observable in the Leuphana sample. Further, those who did not have a university degree – the percentage ranged from around 30 percent at the SDU and OU Helsinki to 43 percent at the Leuphana – were most frequently found in the cluster of the careerists and the degree orientated. In opposite to that respondents with a prior university degree constituted a bigger majority within the cluster belonging to the educational aspirant.

It was also interesting that the careerists, who constituted the majority in all samples, had positive values on all items. Some of the items associated with the degree orientated could also be linked to career goals and were not surprising. But in all the samples, the careerist also had positive values on the items associated with the educational aspirant. This result was in line with Repo’s (2010) findings, that the most important factor which enhances studying at the Open University is the students’ own motivation and interest.

A second interesting fact is that cluster 1 and 2 had high motivations on all or most items whereas cluster 3 had only positive values on some items, with the values mostly around or just slightly above average. This group did not have such clearly definable goals as the others and, since the values were mostly negative, was less motivated. The careerists who attain qualifications for clear career goals seem to be more focused on what they expect to get from university and therefore seem to be more motivated. The educational aspirants had high values on the items associated with interest in the subject and personal development and had negative values on the other items. This group was also highly motivated, but in other areas. However, the cluster seems to be difficult to define and further analysis should include other motivations and differentiations to understand better this group’s aims in attaining university degrees.

In comparison to other studies, it can be concluded that there is no single type of lifelong learner. Students with working experience who enter university for the first time or who re-enter university have different reasons for coming, and according to these, can be sorted into different groups. Universities need to realize this diversity and need to adapt to that with their curriculums, support structures and program designs.

In the present study there were several limitations to be considered when interpreting the results. First, when doing a cluster analysis a combination approach is advised where hierarchical cluster analysis is used to determine the best cluster solution and eliminate outliers and k-means cluster analysis to cluster the observations (Hair 2010, 536). But since in our study we wanted to test whether the theoretically identified types were applicable to our data, the number of clusters was fixed before the analysis. In addition, the cluster analysis was computed for three different universities and countries and therefore a tailor-made solution for each sample would not have been possible for the research question. Cluster analysis is a way of looking at data and is therefore highly dependent on the decisions of the researcher. With a clear understanding of our aim and course of action as here outlined, we are sure that, despite these limitations, the results represent a reliable picture of lifelong learners.

Furthermore, as the discussion of other studies in this area have pointed out, there are many ways to build typologies of lifelong learners and/or non-traditional students. By only focusing on the motivational component, we are well aware that other important aspects were not included. Other factors such as age, educational background, biography or approaches to learning are influential and can add a different perspective or additional information to the categorization. Motivation, however, still depicts an important aspect as it can be seen as a form of goal commitment and builds a strong desire for achievement. In addition it would have been interesting to focus on more European universities which have different models for integrating lifelong learners. We are well aware of the fact that our cluster analysis might then have resulted in a different typology and that we have not fully grasped a “typical” European lifelong learner.

This said, this works fills an important research gap, providing a newly developed typology of lifelong learners from the perspective of why they (re)-entered university. It is hoped that this research offers an informative overview for designers of LLL programs and that through this research they can better understand the needs of this special group.

Despite the country/university differences and limitations, the study has pinpointed an interesting future direction. Lifelong learners are not only a heterogeneous group because of their age, background, biography and levels of education but also because of their aims, motivations and goals. Higher education policy makers and higher education program designers as well as instructors should keep that in mind and this study might help as a first point of departure for new developments in European university continuing education.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Special thanks is given to everyone from the project ”Opening Universities for Lifelong Learning“ and the project ”Open University Lower Saxony“ who was involved in the data collection.

References

Alheit, P., Rheinländer, K., & Watermann, R. (2008). Zwischen Bildungsaufstieg und

Karriere. Studienperspektiven „nicht-traditioneller Studierender“. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 11(4), 577–606.

Allen, D. (1999). Desire to finish college: An empirical link between motivation and persistence. Research in Higher Education, 40(4), 461–485.

Bye, D.; Pushkar, D.; Conway, M. (2007). Motivation, Interest, and Positive Affect in Traditional and Nontraditional Undergraduate Students. Adult Education Quarterly 57 (2), p. 141-158

Crosling, G. M. Heagney, M. & Thomas E. (2009). Improving student retention in higher education: The role of teaching and learning. Australian Universities Review 51 (2), pp. 9-18.

Davies, P. (1995). Adults in higher education: International perspectives on access and participation. London: J. Kingsley.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Eurostat (2013). Gender differences in payment. Retrieved from www.epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Gender_pay_gap_statistics#Gender_pay_gap_levels

Green, A., J. Preston, & Janmaat, J.G. (Eds.) (2006). Models of lifelong learning and the “knowledge society”: Education for competitiveness and social cohesion”. In Education, equality and social cohesion. A comparative analysis, 141-174. Hampshire: Plagrave MacMillan.

Hair, J. F. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Horn, L. J. & Carroll, C. (1996). Nontraditional undergraduates: Trends in enrollment from 1986 to 1992 and persistence and attainment among 1989-90 beginning postsecondary students. Report No. NCES 97-578. Washington, D.C.

Jauhianen, A., Nori, H. & Alho-Malmelin, M. (2007). Various portraits of Finnish open university students. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 51(1) 23-39.

Kasworm, C. E. (1993). Adult higher education from an international perspective. Higher Education, 25(4), 411–423.

Kivilehto, S. (2007). Avoin oppimiselle? Aikuisopiskelijoiden kokemuksia opetus- ja oppimisympäristöistä sekä lähestymistavoista oppimiseen. Kyselytutkimus Helsingin yliopiston avoimen yliopiston opiskelijoille. Julkaisematon Pro gradu –tutkielma. Helsingin yliopisto, Kasvatustiede, Kasvatustieteen laitos. [Open to learning? Students perceptions of teaching-learning environments and approaches to learning. Survey study to Helsinki university’s open university students]. Unpublished Master´s Thesis. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Behavioural Sciences, Department of Education.

Köhler, K., Müller, R., & Remdisch, S. (2012). Leading academic change – successful examples of how universities can respond to the demands of new educational policies and current needs of employers. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation ICERI 2012, 2529-2537.

Müller, R., & Remdisch, S. (2013). Easing transition between academic and vocational routes – A comparison of European models of lifelong learning. Unpublished manuscript.

OECD. (1987). Adults in higher education. Paris: OECD.

Purtilo-Nieminen, S. & Määttä, K. (2011). Admission to university: Narratives of Finnish open university students. International Journal of Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning, 3 (2), 43-55.

Repo, S. (2010) Yhteisöllisyys voimavarana yliopisto-opetuksen ja -opiskelun kehittämisessä. Helsingin yliopisto, Käyttäytymistieteiden laitos, Kasvatustieteellisiä tutkimuksia 228. [A sense of community as a resource for developing university teaching and learning. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Behavioural Sciences, Department of Education.]

Schuetze, H., & Slowey, M. (Eds.). (2012). Global perspectives on higher education and lifelong learners. London: Routledge Chapman & Hall.

Sirkkanen, H. (2008). Opiskelun moninaisia merkityksiä Avoimessa yliopistossa. Diskurssianalyysiä ammatillisen osaamisen kehittämisen motiivista opiskelevien haastattelupuheesta. Julkaisematon Pro gradu –tutkielma. Helsingin yliopisto, Kasvatustiede, Kasvatustieteen laitos. [Various meanings of studying in Open University. Discourse analysis on the interview speech of students with themotive of developing their professional competence]. Unpublished Master´s Thesis. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Behavioural Sciences, Department of Education.

Slowey, M., & Schütze, H. G. (Eds.). (2000). Higher education and lifelong learners: International perspectives on change. London: Routledge Chapmann & Hall.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2012). Zahlen und Fakten. Retrieved from www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/BildungForschungKultur/