This paper presents a method providing adult educators with tools to develop learners' creativity and critical thinking.

Abstract

This paper, in the first two parts, presents the reasons why the role of emotions as well as the use of art in learning is important. Next, the method “Transformative Learning through Aesthetic Experience” is presented. The method aims to provide adult educators with guidelines and tools which might enable them to design art-based training modules which would help them develop learners’ creativity and critical mode of thinking.

The role of emotions in learning

For many years, adult educators, reflecting the dominant influence of the enlightenment and scientific ways of knowing, shared the assumption that education is basically a cognitive process and underestimated the affective sphere of learning. Some of them have been suspicious regarding the manifestation of emotions within the educational settings. Others believed that the emotional dimension of learning falls outside their main scope. And some educators regarded emotions as a concomitant, an accompaniment, in relation to what the real object of learning process is.

The last assumption is a common point within the four theoretical approaches that largely influenced the adult education field during the last fifty years. Firstly, the paradigm of experiential learning (see Kolb, 1984) is most exclusively concerned with the cognitive part of learning. In the Handbook of Kolb, Rubin and Osland (1991) it is stated characteristically:

“There are two goals in the learning process. One is to learn the specifics of a particular subject matter. The other is to learn about one’s own strengths and weaknesses as a learner” (p.59).

Secondly, the approach of andragogy (see Knowles, 1970) considers a learning environment of mutual respect and trust to be necessary, but still the main means to achieve the learning tasks is to give participants responsibility and involve them in experiential techniques.

Thirdly, according to the approach of critical pedagogy (see Freire, 1970) emotions are perceived mainly as a means of ventilating and allowing the learners to focus on the task of critical conscientisation.

Finally, the transformation theory (see Mezirow, 1991) regards emotions as an important component of the perspective transformation process; however it primarily deals with the cognitive side of the acquisition of new insights.

Nevertheless, during all this time important thinkers did not cease to highlight the importance of creating space and giving voice to emotion-laden issues within the environments of adult education. Carl Rogers (1961) claimed that education becomes integrated and its outcomes are deeper when the learners are involved with their whole self: feelings, intuition and cognition. Within this framework, the role of the educator is to act as a facilitator who is alert to the expressions indicative of deep and real personal feelings which exist within the learner. He/ She endeavors to understand them from the person’s point of view, communicates his/her understanding and mutually, expresses his/her feelings in giving feedback. Through this process learning is facilitated, the purposes that have meaning for the participants become elicit, thus significant learning is motivated.

Later on, and especially after mid 80’s, other scholars challenged the cognitive reductionism in the learning process. For instance, Boyd and Myers (1988) argued that the exploration of emotions which emerge from deep within becomes a way to gain access to our internal sources of knowing, thus causing us to (re)consider how we structure meaning. Boud, Keogh and Walker (2002) provided concrete suggestions for helping adult learners work with the feelings arising through the learning contexts. They created a model of reflection process within which the role of feelings is central: First, the learners recall and investigate an experience. At a second stage, they explore their feelings which are related to the experience in order to make the best of the positive elements and transform the negative. Finally, a reexamination of the experience takes place as well as an incorporation of the new elements in the learners’ frame of reference.

Another important theorist of learning, Knud Illeris, stated (2002) that knowledge and emotions constitute an interwoven pattern of function that together characterize the internal process of learning. The cognitive structures are always emotionally obsessed, while the emotional patterns are always affected by cognitive influences. Here, Illeris meets the findings of the brain researchers, such as Goleman (1995) and Damasio (1994): The emotions are intimately bound up with judgments we make and they give our lives meaning. Thus, they have an integral role in our way of understanding the world and occur at all stages of any learning process.

The role of art

Several scholars who share the idea that emotions influence the way we learn to a considerable extend, such as Dewey (1934/1980), Perkins (1994), Greene (2000) and Eisner (1997) provided guidelines on how expressive ways of knowing – especially art based experience – may foster critical and creative learning. This happens because aesthetic experience (a notion understood as the systematic exploration of works of art) encompasses critically reflective and affective dimensions of learning. Specifically, Broudy (1987) argued that the contact with art enlightens the repertory of feelings and simultaneously facilitates the blend of feelings with ideas, enhancing thus the development of cognitive strategies. For these reasons, Broudy calls aesthetic experience a ‘feelingful cognition’ (ibid, p.11).

Another fundamental contribution was provided by Gardner (1990) who suggested that aesthetic experience offers to the participants the possibility to process a variety of symbols through which it is possible to articulate holistic and delicate meanings, leading to the awareness of issues which may not be easily comprehended through merely rational argumentation.

Moreover, Dirkx (2000) considers aesthetic experience as one of the essential ways through which learners may make sense of their underlying emotions and gain a deeper understanding of themselves.

Nevertheless, in spite of the growing recognition of the role of aesthetic experience in various theories of adult learning, a literature review (see ARTiT, 2012a) shows that there are very few methods aiming to provide adult educators with guidelines and tools which might enable them to design training modules that help them develop learners’ creativity and critical mode of thinking through the exploration of works of art.

For this reason, I have suggested a comprehensive method, titled “Transformative Learning through Aesthetic Experience” (Kokkos, 2010), which has been adopted and further developed by the European Grundtvig Multilateral Project ARTiT: Development of innovative methods of training the trainers and implemented in various organizations of adult education in Denmark, Greece, Romania and Sweden.

In the next chapter this method will be presented, as well as the outcomes of the ARTiT project.

The method “Transformative Learning through Aesthetic Experience”

The method is composed by six stages.

First stage: Determination of the need to critically and creatively examine a topic

The first stage refers to the investigation by the educator regarding the need for critical and creative examination of some assumptions the participants share on a topic. The reason for the initiation of this investigation can occur at the beginning or during a training programme, when the educator assumes or somehow finds out that participants consider an assumption as granted and proper, while in reality it represents a stereotype for them or for the whole society.

During this stage, the educator coordinates a discussion aiming to make participants realize the need to reflect on this topic critically and creatively in future sessions.

Example

The example presented, which we will be following though all the stages of the method, is from the application of the method at a Second Chance School in a poor region of Athens. The twelve participants, 25-55 years of age, have not completed mandatory education and have a very poor relation to art. One of them is from Afghanistan and another from Bolivia. One of the subjects they are studying is “Social Literacy”. During the first sessions, the educator realized that some participants expressed xenophobic views and attributed the increase of unemployment in Greece to migrants. This situation led her to think that the topic “foreigner” could be a subject of critical examination. She proposed the idea to the group and they accepted. It was decided that discussions on the issue would be based on artworks which would function as triggers for the discourse. Four sessions were to take place of two hours each. This way, the first stage of the method’s application was completed.

Second stage: The participants express their ideas about the topic

At this stage, the educator asks everyone to reply in writing to some open questions. This is done in order to obtain the material needed to formulate a strategy for the development of critical and creative thinking on the topic. In addition, the recording of the original ideas will serve later in the final stage of the process, when they will be compared to the ideas which originated from it.

Example (continued)

The educator asked from the participants to write, in two groups, their aspects on the question “What does a foreigner living in our neighborhood mean to us?” The first group replied: “For us there is no problem. Moreover, these people came to our country seeking work.” And the second group: “Some of them can cause problems, thefts, murders, etc. We must learn to live together but they shouldn’t take the jobs from the Greeks.”

Third stage: Identification of critical questions that should be approached

The educator, after studying the ideas expressed by the participants, negotiated with them a variety of critical questions that should be examined in relation to the topic at hand.

Example (continued)

The learning group identified, through a vivid discourse, three critical questions:

a. Once a foreigner, always a foreigner?

b. Do immigrants threaten our way of living?

c. To which extent can we understand the way of thinking/ feeling of immigrants?

Fourth stage: Selecting works of art and linking them to the critical questions

The educator, in cooperation with the group, identifies various pieces of all forms of art, which could serve as triggers for the elaboration of the various dimensions of the topic chosen to be examined. The meanings that will be drawn from them should be related to the content of the critical questions that have been formulated during the previous stage.

A basic element of the method at this point is that the works of art to be chosen should be of aesthetic value, not trivial or conventional ones. This idea is based on the ideas of important theorists of education and art, such as Adorno (1986), Greene (2000), Marcuse (1978), Perkins (1994) and others, who argue that our contact with works of art of aesthetic value creates numerous triggers for thinking critically, as they are full of meanings and are amenable to multiple interpretations. Conversely, the contact with mass culture works prevents the development of critical thinking, as it addicts the participants to simplistic approaches, idealized messages and stereotypical symbols, entrapping them in given, ordinary ways of making sense.

However, the method takes the “warning” by Bourdieu and Darbel seriously in mind, that comprehending remarkable works of art often requires the ability to “decipher them”(Bourdieu & Darbel, 1991, pp. 38-39), therefore their use within educational settings has the risk of discouraging social groups which lack a certain cultural background. For this reason, the method suggests three criteria for choosing the works of art to be used:

a) they should offer a wide range of triggers for critical thinking on the topics at hand; b) they should be mainly of representational character, in order to be comprehended by all the learners; c) they should relate to the life experiences of the learners to make them interested in the process.

Additionally, the content of the chosen artworks should be clearly connected to the critical questions which are investigated by the learning group.

One more important element during the fourth stage of the method is the active participation of the learners while choosing the works of art. There are several alternatives, such as: the educator suggests to the participants a variety of works of art and they identify those of their preference; the educator suggests the sources where learners might find the necessary works of art; the educator provides participants with criteria for the search and selection of the works of art.

Example (continued)

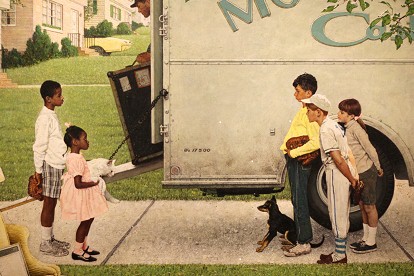

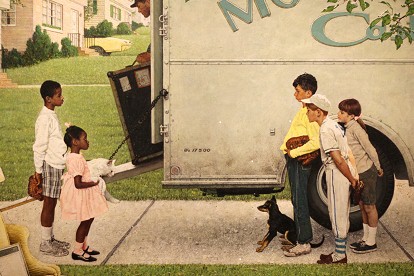

The educator proposed to the group to choose two works of art from the following: The paintings New Kids in the Neighborhood by Norman Rockwell and The Balkan Mirror by Krassimir Kolev, the film Entre les Murs by Laurent Cantent, and the poem A Bedtime Story by Mitsuye Yamada. The group chose the first and the last one.

New Kids in the Neighborhood (top), Balkan Mirror (bottom)

A BEDTIME STORY

Once upon a time,

an old Japanese legend

goes as told

by Papa,

an old woman traveled through

many small villages

seeking refuge

for the night.

Each door opened

a sliver

in answer to her knock

then closed.

Unable to walk

any further

she wearily climbed a hill

found a clearing

and there lay down to rest

a few moments to catch

her breath.

The village town below

lay asleep except

for a few starlike lights.

Suddenly the clouds opened

and a full moon came into view

over the town.

The old woman sat up

turned toward

the village town

and in supplication

called out

Thank you people

of the village,

if it had not been for your

kindness

in refusing me a bed

for the night

these humble eyes would never

have seen this

memorable sight.

Papa paused, I waited.

In the comfort of our

Hill top home in Seattle

overlooking the valley,

I shouted

“That’s the END”

At the second part of the fourth stage, the educator prepared a Table (Table 1 below) demonstrating the way in which the content of each chosen work of art might be connected to the content of one or more of the critical questions mentioned in the Third stage.

Fifth stage: Elaborating the works of art and linking them to the critical questions

At this stage, the educator coordinates a process during which – through the systematic exploration of chosen works of art – an approach of the critical questions is conducted. The steps are as follow:

a. The first work of art is explored (or/and a second one).

b. Out of the ideas arising, the group finds reasons to expand on one or more critical questions.

c. This process could be continued with the elaboration of more works of art and more critical questions.

During the elaboration process of each work of art, it is important for each learning group to draw their own meaning from it. The educator should explain that there is no “authentic” interpretation of artworks and should encourage the participants to use their creativity while working on them. Also, discourse on an artwork might not examine extensively the technical or morphological elements (e.g. the use of colours of light in paintings, the use of montage of photography in films, etc). This is important so the learners who are not familiarized with art don’t feel that they can’t contribute to the conversation. However, in order to make the process of understanding a work of art more integral, the participants should be encouraged to engage to a certain degree with the elaboration of technical elements, depending on their disposition and interest.

At this point, our experience from the application of ARTiT showed that if the exploration of some morphological components is done carefully and progressively (e.g. concerning the role of music in a film or the role of colours in a painting), the interest of the learners is more intense.

Finally, in order to make the exploration of each work of art systematic, a four-phases technique is applied, which was proposed by D. Perkins (1994) and has been the cornerstone of Project Zero of Harvard University.

During the first phase, the facilitator asks the learners to have “looking time” in order to give the work of art a chance to show itself to us. At the second phase, learners are stimulated to search for characteristics of the artwork that make their observation broader, to notice sides that would otherwise remain invisible. For instance, they might look for surprises, symbolisms, cultural and social connections. At the third phase, the participants investigate more analytically the artwork by exploring deeper what surprised, interested or puzzled them. Finally, in the fourth phase they review the work holistically, marshalling all they have discovered.

Example (continued)

The learning group began to apply the first phase of Perkins’ model, by exploring the painting New Kids in the Neighborhood (I personally participated in the process as an observer). The educator posed triggering questions such as: “What do you see? Let your eye work for you”… “Notice interesting features: Let’s label them”… The learners quoted: “I see two groups of children”; “Chairs, houses”; “The children are calm”; “It is a rich neighborhood, there are nice houses, lawn, an expensive car”; “We don’t know if the kids live in the same neighborhood”…

Following, the educator introduced the second phase of the model: “Look more carefully. Is there something that strikes you, something that seems odd to you?”; “Keep looking, discover new features”; “Look for surprises”; “Look for symbolism and meaning”.

The participants responded: “The white people are driving the blacks away from the neighborhood”; “No, it could be that the black people are coming to settle”; “The white children are looking at the black ones with surprise, like they are saying: ‘Who are you? What are you doing here? Why are you that colour?’ ”; “The white kids have a black dog and the black kids have a white cat. That shows that the difference between them is not that big.”; “The clothes of the black children are more expensive, they are nicer.”; “Of course there are differences between the two groups, but they are not fighting, as it usually happens.”

Subsequently, the educator used questions as triggers of the third phase, such as: “Go back to something that surprised you: Was there a message?”; “Articulate questions and possible resolutions. What do they imply?”; “Look for well evidenced conclusions”. Some answers of the participants mentioned: “Look, the white and the black kids are holding a base-ball glove… They want to get acquainted, to play together”; “They want to live together”; “But I see a separating line in front of the black children…Something is limiting them”; “The black children are closer to the line than the white kids”; “But behind the white kids there is also a line setting the borders of where they are standing… The artist didn’t do that accidentally”.

Finally, while applying the fourth phase of Perkin’s model, the educator asked from the participants to re-see the whole work and marshal all they have discovered. As they stated: “The painting shows that not only white people have nice clothes and are educated, but also black people”; “The colour doesn’t make the person”.

After the elaboration of the painting, a relevant approach was made concerning the poem A Bedtime Story. Then the educator asked the participants to relate the ideas that emerged from the elaboration of both artworks to the three critical questions. The participants quoted: “We all come from somewhere and we will all end up somewhere together. There is no reason for hate on the planet”; “Our days, we are more afraid of Neo-Nazi political parties and of Greeks rather than foreigners”; “The media are responsible for creating xenophobia. They control our consciousness”. Educator: “How may we react?”; Responses: “We must resist”; “There shouldn’t be any walls between us”; “We are the ones who create those walls”; “Look at our situation here at the school: Why is anyone considered to be any lesser for not finishing high school?”

Sixth stage: Reflection on the experience

The ideas resulting from the process of steps b and c of the fifth stage are recorded – either orally or in paper. The final assumptions are compared with those expressed earlier, in the 2nd stage.

Example (continued)

The participants – in small groups – answered once again (written) to the question “What does a foreigner living in our neighborhood mean to us?” The first group wrote: “Our disposition is positive, as it gives us the opportunity to meet different cultures. However, we want them to respect us in order to integrate into society”. And the second group: “We don’t have a problem with foreigners. We often learn about the way of living in their countries. We have noticed lately that because of the crisis many economic migrants become garbage collectors in order to survive”.

Outcomes from the evaluation of ARTiT

The ARTiT Evaluation Report (2012b) showed that the application of the method contributed significantly to the empowerment of critical/creative thinking of the learners. Moreover, the participants have been gradually familiarized with art. At the beginning of the project, when they were asked how they felt about using an art-based method, almost half (43%) expressed a negative or ambivalent disposition. However, at the end of the project, to the question “Did you like the training through the use of works of art?” 87% answered “very much” or “a lot”. The justification of those who had expressed these opinions was the following (% of the total of their statements):

As stated by the learners:

“I believe that using art in education cultivates imagination, emotional and experiential learning. It broadens mental horizons and critical thinking.”

“To get the time to think and reflect and be asked questions that make you think even deeper is very stimulating. The discussions we‘ve had were very rewarding.”

“It is a very good way to make people think outside the box.”

“I never looked at a work of art like this, and I’m sure that this method could change people.”

The Evaluation Report comments (ARTiT, 2012b, p. 20):

“The answers to this specific issue of the program’s methodology revealed two important elements. It is evident that the program gave to the learners the opportunity to develop their creative / critical thinking or to approach several issues in a new or / and deeper way. Conversely, the participation of the learners in the program gave them the opportunity to get familiarized with art and appreciate the contribution of art to the learning process.”

Epilogue

The results from the application of the method through the ARTiT project are encouraging. It is now evident that the method can be applied effectively at a wide range of adult education agencies and it can be a basic component for teaching a large variety of topics (during the ARTiT project, art-based learning was used for teaching foreign languages, job search techniques, leadership, immigration, inter-cultural relations, mass communication, work and life balance, poverty and marginalization, gender relationships, train the trainers, etc). It is especially important that the learners who were not familiarized with artworks not only accepted to approach some in a systematic way, but they also enjoyed seeking their meanings.

These outcomes demonstrate that there may be a creative possibility within the framework of lifelong learning in Europe: It would be possible to use art, provided that certain methodological conditions are met, to contribute so that learning processes combine the cognitive and the affective dimension. Moreover, it would be possible for the social groups who have not developed a relationship with art–due to the process of their socialization- to expand their cultural awareness and expression.

References

Adorno, T. (1986). Aesthetic Theory. New York, N.Y.: Routledge &Kegan Paul.

ARTiT (2012). a) The ARTiT Methodology and Modules. b) Evaluation Report. Retrieved October 15, 2012 from www.artit.eu.

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (2002). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. New York, N.Y.: Kogan Page.

Bourdieu, P., Darbel, A. (1991). The Love of Art: European Art Museums and their Public. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Boyd, R.D., & Myers, J.G. (1988). Transformative Education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 7, 261-284.

Broudy, H. (1987). The Role of Imagery in Learning. Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Centre for Education in the Arts.

Damasio, A. (1994). Descarte’s Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. New York, N.Y.:Grosset/ Patnam.

Dewey, J. (1934 /1980). Art as Experience. New York, N.Y.:The Penguin Group.

Dirkx, J. (2000). Transformative Learning and the Journey of Individuation. ERIC Digest, no. 223. ERIC Document Reproduction Service, No ED6 448305.

Eisner, E. (1997). The Enlightened Eye: Qualitative Inquiry and the Enhancement of Educational Practice. New York, N.Y.: Merrill Publishing Company.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, N.Y.: Herder and Herder.

Gardner, H. (1990). Art Education and Human Development. Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Education Institute for the Arts.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than I.Q. New York, N.Y.: Bantam Books.

Greene, M. (2000). Releasing the Imagination. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Illeris, K. (2002). The Three Dimensions of Learning. Roskilde University Press.

Knowles, M. (1970). The Modern Practice of Adult Education. Andragogy versus Pedagogy. New York, N.Y.:Association Press.

Kokkos, A. (2010). Transformative Learning Through Aesthetic Experience: Towards a Comprehensive Method. Journal of Transformative Education, 8, 153-177. Retrieved December 12, 2010 from http://jtd.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/06/29/1541344610397663.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the source of Learning and Development. New York, N.Y.: Prentice- Hall.

Kolb, D., Rubin, I., & Osland, J. (19915). Organizational Behavior: An Experiential Approach. New York, N.Y.: Prentice- Hall.

Marcuse, H. (1978). The aesthetic dimension. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Perkins, D. (1994). The Intelligent Eye. Los Angeles, CA: Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Rogers, C. (1961). On Becoming a Person. Boston, MA: Houghton- Mifflin.