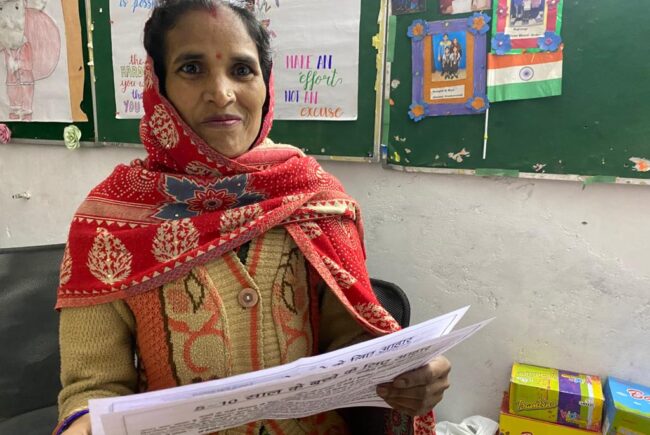

Mamta is learning about basic hygiene and nutrition at her local school. Photo: Pia Heikkilä

Mamta is learning about basic hygiene and nutrition at her local school. Photo: Pia Heikkilä

New Literacy policy in India aims at improving learning amongst the women and disadvantaged. To achieve the goal to become a leading economic powerhouse for the 21st century, the country is aiming to make sure that every Indian can read.

Mamta is holding a piece of paper with pictures of food on it. She has come to a local school in Delhi’s Ghaziabad where she can learn about basic hygiene and nutrition.

“Today we learnt about handwashing, and different proteins and why they are important to the body,” she says.

She has never learnt to read or write but is able to do basic counting. The mother-of-five is unsure about her age but thinks she around 40 years of age.

“If I need help reading, I ask one of my children to help,” she says.

Women listen attentively in a class as they want to improve their lives. Photo: Pia Heikkilä

India has millions of women like Mamta. Their schooling is either non-existent or minimal as they get married off at a young age due to poverty and never return to education due to lack of affordable educational facilities. They rely on picture-based communication and their families to help them with everyday matters.

Mamta’s classes are organised by a Delhi-based NGO, the Love and Care Foundation. She is one of the many women and children who get educational help from the foundation for free.

“The women are very eager to learn and very motivated, and we teach them everyday practicalities. Their priority is to see their children educated, even though the family’s finances don’t often allow that,” says the founder of Love and Care Sunjoo Dadroo.

“They never got the opportunity to study but they do understand the value of education and how it can change their children’s lives,” he adds.

New policy to boost literacy

India is trying hard to become a leading economic powerhouse for the 21st century. One of the key aims the country has is to educate its people and make sure every Indian can read.

The country has the world’s largest number of illiterate adults with approximately 280 million adults unable to read. According to Oxfam International, this is 37 per cent of the total illiterate population of the world.

To increase literacy and provide adult education, India has revamped its National Education Policy and, as a part of it, the country’s government has approved the New India Literacy Programme for the next five years.

The programme wants to focus on the women and disadvantaged.

The programme wants to focus on the women and disadvantaged. Women are the country’s hidden economic potential as fewer than one third of them work outside the home.

Teaching adults, especially women, is not an easy task, however. The socioeconomic factor is the key in India when it comes to achieving literacy.

The more money a family has to invest in its child’s education, the more likely he or she is to be able to read and empower him or herself. But the matter is more complex than that.

Indian women are often excluded from learning as the families prefer girls to marry and start a family at a young age. Girls are too often seen as a burden.

Winning the trust of the community is key

The difficulty is trying to convince the conservative communities, and especially the male members in it to let women take up studying again, say Dadroo.

“When you are trying to educate the community’s women, you must start with groundwork. We must prove why it’s good for them to learn. Then you start creating trust,” he says.

Whilst every citizen of India has a right to basic education according to the country’s constitution, in practice it is different. Literacy in India has had a gender disparity for many years.

The majority of the unschooled are still, even today, women.

Sunjoo Dadroo sees creating trust as key to women’s learning. Photo: Pia Heikkilä

“Women need their husband’s approval to attend classes and first we need to make sure they know who we are.”

Obstacles to learning are deeply rooted in the patriarchal culture that openly discriminates against women, and families don’t see anything wrong with not sending their girl child to school.

“Here, men don’t like to let the women out of the house and have independence, so we begin by explaining how it is beneficial for the entire family that the women are educated,” says Dadroo.

Obstacles to learning are deeply rooted in the patriarchal culture.

India has been trying to improve its literacy for a long time. The original attempt was called National Literacy Mission, a nationwide programme started by the Government of India in 1988, which aimed to educate 80 million adults.

Officially India’s literacy rate for 2018 was 74.37 percent, a 5.07 percent increase from 2011, according to data from the government.

But some critics of the state’s education policy say unofficially it is hard to make precise calculations on how many adults can read. One of the main reasons for that is that there has not been a full census done in the country since 2011 and the next census is not due until 2024 due to political disagreements. India does not know how many people can read, because it does not even know how many people there are in the country.

Divisions not only exist between socio-economic status or gender, but geography also matters as there are vast differences between states too. Largely the country’s south is seen as more literate and states such as Kerala boasts that over 95 per cent of its people can read. On the other hand, northern states such as Bihar, which has poor access to schools and a generally lower standard of living, has an estimated literacy rate as low as 63 per cent.

Food as motivation

In the next room at Ghaziabad school, a noisy crowd of pre-school children are getting their midday meal. Vegetable curry, rice, rotis and dahl disappear into hungry little mouths.

“One of the ways to motivate people to learn is to offer their children free food,” Dadroo says.

The community in Ghaziabad is so poor that this school meal might be the only time in a day the children are fed, says Dadroo.

For Mamta, learning with the help of pictures is fine for now. As a home-maker, she is mainly concerned about her children and has managed without being able to read for all her life.

In India, when the state fails to reach all levels of the community, it is NGOs like Love and Care Foundation that step in with basic services. No-one knows how many NGOs there are in Delhi alone working in the field of adult literacy.

Love and Care Foundation aims to plug the gap between state education and to help the disadvantaged communities by motivating the mothers to get involved in learning.

“India’s literacy situation is changing, and we will get there one day. But it will take time,” Dadroo says.

Author